-

Director’s Notes and Synopses on Three Musical Tales

By Kiersten HayPosted in Pyramus and ThisbeBy Christopher Alden

A new Canadian opera, Pyramus and Thisbe by Barbara Monk Feldman, receives its world premiere today (appearing along with Monteverdi's Lamento d’Arianna and Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda). This modern triple bill not only features a striking new opera, but manages to cover almost the entire span of operatic history throughout its three parts. Director Christopher Alden expands on some of the historical and thematic ties between these pieces in his program notes.

During the past 400 or so years since it was first “invented” in Renaissance Italy, the operatic art form has always had an intriguingly schizophrenic nature. On one hand, it has always depended for its survival on the support of the rich and powerful patrons for whom a night at the opera is just as much a social as it is an esthetic experience. But on the other hand, with its magically alchemical mingling of words and music, opera has managed to penetrate into dark, mysterious and even painful realms of human experience, soothing its audience with sweet sounds while it tells its subversive stories.

The three musical tales which share the stage in tonight’s “exotic and irrational entertainment” (as Dr. Samuel Johnson described it) span the entire history of opera, but share similar themes. Claudio Monteverdi’s and Barbara Monk Feldman’s pieces, all drawn from classical/mythological sources, address the spikily ambivalent nature of male/female relationships, the societal forces which conspire to throw roadblocks in the way of the deep human need to find spiritual and physical connection with another human being, and the eternal quest of us mortal beings to move beyond our ego fixations and find a richer and more organic relationship with existence.

Lamento d’Arianna, the only existing fragment from Monteverdi’s second opera, became the composer’s most celebrated and emulated piece in his day. Drawn from Ovid and other classical sources, the story tells of the Cretan princess, Ariadne, who falls in love with Theseus of Thebes, then helps him escape from the Labyrinth and kill her half-brother, the monstrous Minotaur. After this betrayal of her culture, Ariadne flees her homeland with Theseus, who rewards her by summarily dumping her on the first island they pass. He sails victoriously back to his kingdom as she laments her abandonment, alternating between extremes of sorrow, anger, fear, self-pity and desolation.

From a modern feminist perspective, Ariadne’s predicament is the perfect metaphor of a woman’s position in our patriarchal world. She trades her heritage, throne and power for a relationship with a powerful man. Worried that his people will not accept a foreign princess as their queen, he leaves her in the dust after she has given up everything for him, placing a higher value on his societal role than on hers. Ironically, audiences of Monteverdi’s time might well have perceived Ariadne’s story as teaching a moral lesson wherein a dangerously proud woman is justly punished for defying gender roles, betraying her father and choosing her own mate.

In Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, the “heroine” confronts the Christian patriarchy head on. Taken from an episode in Torquato Tasso’s epic poem, Gerusalemme Liberata, the piece thrillingly enacts the encounter of the Christian crusader knight Tancredi by the walls of Jerusalem with a mysterious Saracen opponent. They fight and the unknown infidel warrior is mortally wounded. Dying, the stranger asks to be baptized and is ultimately recognized by the traumatized Tancredi as his beloved Clorinda. The knock-out-drag-out fight to the death on the marital battlefield in Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? has nothing on Monteverdi’s terse depiction of male/female aggression. It is the definitive dramatization of the Battle of the Sexes, portraying men and women as two separate species, forever unknowable to each other, locked in an enmity as everlasting as that of Christians and Muslims endlessly fighting for possession of the holy city Jerusalem. Tasso’s metaphorical joust functions on multiple levels, showing us in painstaking detail how each man kills the thing he loves. The Narrator tells us that “Three times the knight holds the woman/in his strong arms and as often/she escapes his tenacious embrace,/the embrace of a proud enemy and not of a lover.” Yet there is something undeniably erotic about this sadomasochistic encounter between ambivalent lovers, suggesting that the flip side of the fearful mysteries and secrets which men and women (or people in general) hide from each other is actually an intense attraction to the mysteriously seductive Other. From a modern cultural perspective, it seems a shame that Tasso’s gloriously fearless female Saracen Clorinda is not only put down by the male crusader Tancredi but, before dying, begs to be baptized so that she may convert to his faith (once again depicting the inevitable triumph of patriarchal Christianity). But who can deny the beauty of this denouement, which sings so exquisitely of forgiveness and transcendence?

Pyramus and Thisbe is all about transcendence, even going so far as to transcend a conventional narrative structure in order to work its subtle magic as a theatre piece built not on action but on contemplation, stillness, even silence. Barbara Monk Feldman was initially inspired to write the opera not so much by the Pyramus and Thisbe story (recounted by Ovid, then famously used by Shakespeare as the script mercilessly but mirthfully mangled by the mechanicals in A Midsummer Night’s Dream), but by Nicolas Poussin’s painting depicting a pivotal moment in the tragic story.

The composer’s libretto is a fascinating collage of fragments of disparate texts which does not attempt to recount Ovid’s tale in a literal manner. The story concerns a pair of lovers separated by a wall which their fathers, mortal enemies, have constructed. The lovers, having found a chink in the wall, use it to communicate with each other, eventually devising a secret plan to meet by night. Thisbe is the first to arrive at the agreed-upon location, but is frightened away when she sees a lioness approach. Escaping, she drops her veil, which the lioness rips apart, leaving it torn and smeared in the blood from a recent kill. After the lioness departs, Pyramus arrives, sees the torn and bloody veil, and assumes that Thisbe has been murdered. Grief-stricken, he stabs himself only moments before Thisbe returns to find her dying lover. She then uses his bloody dagger to end her own life. This tale (which Shakespeare also used as the basis for the plot of Romeo and Juliet) is a classic reminder that “the course of true love never did run smooth.” With its warring fathers, veritable Berlin Wall and climactic Liebestod, Ovid’s story suggests that the true union of two souls is impossible in this imperfect world, achievable only after death.

Ovid’s story is used as a jumping-off point to address the wider issue of coming to terms with existence. The first section, using a Faulkner text about a man collapsing the moment after he has been fatally shot, shows us Pyramus in the moment of his suicide, struggling with his own death-wish. The second section is taken from the opening poem of Dark Night of the Soul, a religious text by the 16th-century Spanish mystic, St. John of the Cross. It equates Thisbe’s secret nocturnal journey to meet Pyramus with the journey of the soul to its blissful union with God, achieved through spiritual negation of worldly things. The rapturous atmosphere of this episode is tempered by Thisbe’s awareness of worldly danger (the lioness). The pivotal moment in the opera occurs at the beginning of the third section, when Thisbe, in a text by the 20th-century German psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers, says to Pyramus, “Don’t sacrifice yourself, be yourself!” In doing so, she urges him to transcend the endless mortal cycles of desire, aggression and ego fixation which are exemplified in the stories of tormented human interactions, like those of Ariadne and Theseus and Tancredi and Clorinda. When, climactically, Pyramus responds with stanzas from Rilke’s ecstatic Sonnets to Orpheus, he takes up Thisbe’s challenge and steps outside the box of traditionally dogmatic patriarchal assumptions to embrace a wider connection to existence, moving beyond his fear of the unknown, the unconscious, and finally of death itself.

Pyramus and Thisbe premieres October 20, 2015 and runs until November 7, 2015. For more information click here.

To buy tickets, click here.

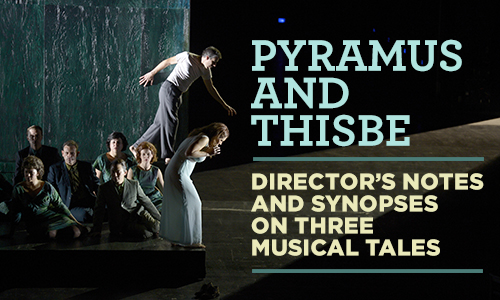

Phillip Addis as Pyramus and Krisztina Szabó as Thisbe in the Canadian Opera Company’s world premiere production of Pyramus and Thisbe (with Lamento d’Arianna and Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda), 2015. Photo: Gary Beechey