-

Looking at Salome

By Danielle D'OrnellasPosted in 2012/2013By Nikita Gourski, Development Communications Officer

In 1994, Canadian film director Atom Egoyan won international recognition for his film Exotica, a provocative meditation on erotic obsession and psychological trauma explored through the relationship of a nightclub dancer and her male client.

Shortly after Exotica’s release, the Canadian Opera Company approached Egoyan with an offer to direct an opera, a story so thematically saturated with voyeurism it seemed ideal for the young filmmaker’s sensibility: Richard Strauss’s Salome.

Unveiled in 1996, Egoyan’s production simultaneously recognized the deeply disturbing matter of the opera – a work that has inflamed scandal since its 1905 world premiere – while offering a fresh reading responsive to our contemporary culture. Rather than a first-century palace in Judea, Egoyan set the action in an abstract and foreboding environment, something between a spa and a sanatorium. Derek McLane’s set design is built around a diagonal plane tilted at a dangerously steep angle, with Jochanaan (John the Baptist) imprisoned underneath the floorboards instead of the subterranean cistern in which he’s traditionally kept.

Egoyan’s approach focused on the complex circuitry of voyeurism, made explicit in the libretto, and followed it to its disconcerting psychological depths. From the first lines of the opera – “How beautiful the Princess Salome is tonight,” repeated obsessively by the young Syrian Narraboth – the process of looking is established as a dominant psychological theme in Salome. Characters are compulsively observing others, or else being looked at themselves, held visually as objects within a matrix of frustrated desire. “The Page is obsessed with Narraboth, who doesn’t return her gaze; Narraboth is obsessed with Salome, who doesn’t return his gaze; and Salome is obsessed with Jochanaan, who doesn’t return her gaze,” Egoyan says, describing the opera’s gridiron pattern of erotic fixation.

To get at the heart of all this looking, Egoyan’s production makes use of surveillance equipment, as well as projected film and video images. The guards, for example, become camera-wielding soldiers, whose official “watching” is less about patrolling the perimeter and more about deploying modern technology to direct a collective gaze onto objects of sensual interest: usually Salome. In fact, before we ever see the teenaged princess onstage in the flesh, we encounter a filmed image of her in a series of unsettling shots set in a spa’s mud baths.

Similarly, when Jochanaan berates members of Salome’s family from offstage, a large video screen positioned behind the singers shows a live feed of his mouth in close-up. The disembodied projection anticipates Salome’s fetishistic dissecting of Jochanaan’s body parts – skin, hair, mouth – into isolated objects of lust, but it also prefigures the actual, physical decapitation of the prophet. Incorporating film projection in this context elaborates the thread of continuity that runs between the predatory look and the act of unimaginable violence.

In this opera, looking is never benevolent. From Salome’s opening remarks about the lascivious gaze of her stepfather Herod – “those mole’s eyes… under his quivering eyelids” that look at her “like that” – to the Page warning Narraboth that it’s “very dangerous to look at a human face in such a way,” the desiring gaze has a throbbing underside that threatens to devour and consume.

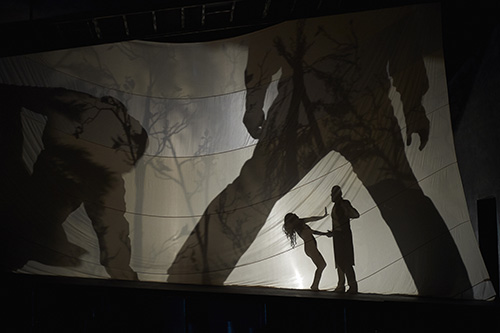

Nowhere is this truer than the opera’s narrative pivot: the Dance of the Seven Veils. Egoyan’s innovative account gives a dramatic weight and clarity to Salome’s psychology that few interpretations could rival. On a screen created by the billowing skirts of the princess, who is lifted on a swing high up into the rafters, we see “home movies” of the young Salome. In these moments, she is a girl in a world of paper dolls, living through childhood. But we also catch silhouetted glimpses of a disturbing act committed in the shadows, possibly in the near past, but maybe right now: she is being raped by a gang of men. We realize that Salome’s stepfather Herod oversees the entire sexual atrocity, watching it and thereby giving it licence.

“[Violence] doesn’t come out of nowhere,” Egoyan observes, “and we’ve seen that with abused victims: there is a repetition of the way that they have been treated.” Using the dance to chronicle a history of terrifying acts makes Salome’s subsequent demand for Jochanaan’s head psychologically credible and dramatically focused. Instead of showing the prototypical femme fatale – “an unbridled sexuality that leads to ruin,” as Egoyan says – the production depicts an “abused, traumatized character."

The results carry a sobering impact. Egoyan’s production issues a challenge: it asks us to treat seriously – and understand – how anyone, including a young girl, could instigate such horrific violence.

This article is published in our spring house program. Click here to read the issue online.

Photos: (top) (l – r) Hanna Schwarz as Herodias and Erika Sunnegårdh as Salome; (middle) (l – r) Nathaniel Peake as Narraboth, Maya Lahyani as the Page of Herodias, Evan Boyer as First Soldier and Sam Handley as Second Soldier; (bottom) Dance of the Seven Veils scene. Photos from the Canadian Opera Company's 2013 production of Salome. Photos by Michael Cooper.